Ulysses takes the warrior Ulysses (the Roman name for Odysseus) as its focus, and – using the then-new form of the dramatic monologue, which Tennyson helped to pioneer – reveals an ageing king who, having returned from the Trojan war, yearns to don his armour again and ride off in search of battle, glory, and adventure (leaving his poor wife Penelope behind).

Read Also: The Higher Pantheism a Poem By Alfred, Lord Tennyson

The poem ends with Ulysses triumphantly announcing his intention to sail off again on yet more adventures. After being away from home for ten years while fighting in the Trojan War, and then taking ten years to get back home to the island of Ithaca to his family (having many adventures along the way, which Homer writes about in the Odyssey), Ulysses/Odysseus feels ill at ease at home.

The civilian’s life is not for him: he is made for battle and adventure and voyaging (even though, in the Odyssey, he manifestly hates travelling on the sea), and will never be content to be the stay-at-home king with a wife and son, living out the rest of his years on Ithaca and enjoying ‘the quiet life’.

Read Also: Complete Destruction a Poem By William Carlos Williams

Ulysses Analysis

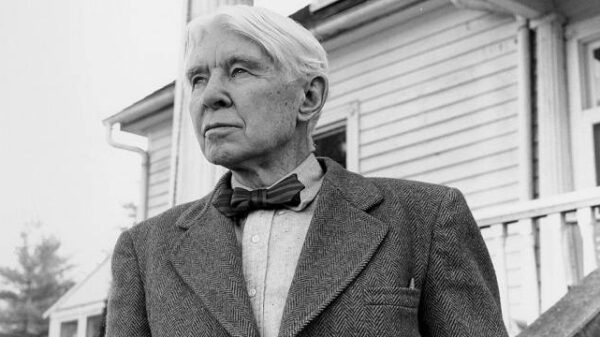

Alfred, Lord Tennyson once remarked that the poem Ulysses was ‘written under the sense of loss and that all had gone by, but that still life must be fought out to the end.’ In particular, the ‘sense of loss’ Tennyson was coping with (and barely at that) was the death of Arthur Henry Hallam, his university friend from their student days at Cambridge, who had dropped down dead, aged just 22, in 1833.

Indeed, Tennyson claimed that ‘Ulysses’ was ‘more written with the feeling of his loss upon me than many poems in In Memoriam.’ In Memoriam was Tennyson’s great elegy for his friend, but ‘Ulysses’ had its roots even more firmly in Tennyson’s private grief for his friend.

Read Also: Crossing The Bar a Poem By Alfred, Lord Tennyson

We need to bear in mind Tennyson’s remarks in any analysis of ‘Ulysses’. A commentary on the poem that neglects to address the role that Hallam’s death had in inspiring this poem about courage and fighting on, and fighting even when one personally sees no point in such things because all that mattered has been lost, is likely to miss the real message of ‘Ulysses’: that though we may personally be ‘made weak by time and fate’ we must remain ‘strong in will’ and, in the words of Churchill, ‘KBO’ (keep b**gering on).

But how convincing we find Ulysses’ act of courage here can be questioned. Around the same time as he wrote ‘Ulysses’, Tennyson also wrote another Ulysses-inspired poem, ‘The Lotos-Eaters’, which begins with that very word, ‘Courage!’, spoken by Ulysses/Odysseus himself.

Read Also: The Charge of the Light Brigade By Alfred, Lord Tennyson

The poem that follows, however, sees Odysseus’ crew sink into lethargy and listlessness as they fall under the spell of the lotus fruit. Odysseus’ call for ‘courage’ there promptly gives way to inactivity and passivity, as his men become slaves to the drug of the lotus. And of In Memoriam, already mentioned, Tennyson once famously said that it was more hopeful than he was himself (among other things, he struggled to maintain the hope that he and Hallam would see each other in heaven).

We might analyse the Ulysses of Tennyson’s poem in quite another way: as talking big words which he is unable to live up to. As at least one academic has said, there is something of the ageing fighter saying he’s going to make a comeback to the boxing ring, convinced (deluded) that he’s still ‘got it’, about Ulysses in Tennyson’s poem.

Read Also: In Memoriam a Poem By Alfred, Lord Tennyson

He doesn’t feel at home on Ithaca (describing himself as an ‘idle king’ surrounded by ‘barren crags’, with ‘an aged wife’ next to him, ruling over a people who ‘know not me’), so his determination to sail off beyond the sunset may owe more to his inability to adapt to ordinary life than to his sincere belief that he will be able to go on striving, seeking, and finding forever.

Or, if he does believe it, he may be deluding himself. As one Victorian commentator, Goldwin Smith, put it in 1855, Ulysses wants to take to the seas again ‘merely to relieve his ennui’ and that ‘he roams aimlessly’ since ‘he intends to roam, but stands for ever a listless and melancholy figure on the shore.’

And even in the poem that inspired Tennyson’s own, Homer’s Odyssey, Odysseus spends more time stranded on an island or sitting about than he does actually doing something. He spent seven of the ten years it took him to get home from the Trojan War a captive on Calypso’s island. In the last analysis, readers of Tennyson’s ‘Ulysses’ may find that he speaks of doing things far better than actually doing them.

Cc: Deserved

Poet Nazir is a writer and an editor here on ThePoetsHub. Outside this space, he works as a poet, screenwriter, author, relationship adviser and a reader. He is also the founder & lead director of PNSP Studios, a film production firm.